Thinkstock

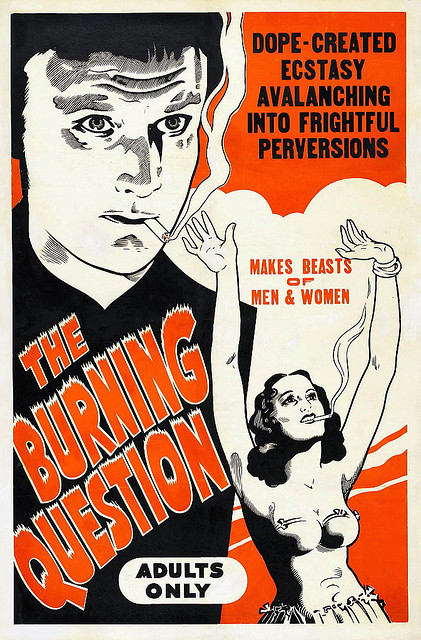

In many ways, marijuana is a quintessential token of passive rebellion. Sure, it's illegal (in most states) but it's a medicinally utilized plant (herb?) that's slowly but surely becoming destigmatized. Which, in the light of fairly recent extremist propaganda of past generations (which successfully attached an exaggerated aspect of danger to this potent little plant), speaks volumes to our progression. Don't believe me? Check out Reefer Madness on Netflix sometime. Even if  you've vowed never to rip a bong, it will seem over the top—to say the least.

you've vowed never to rip a bong, it will seem over the top—to say the least.

Interestingly enough, despite the misinformation and general controversy surrounding the proffering and puffing of pot, history suggests that bans are more deadly than the substance itself.

Now, even the New York Times has taken up the torch of speaking out against the illegality of weed, dedicating an entire series to the topic—High Time: An Editorial Series on Marijuana Legalization. Specifically, it's likened the movement to the end of Prohibition during the late-early 20th century:

It took 13 years for the United States to come to its senses and end Prohibition, 13 years in which people kept drinking, otherwise law-abiding citizens became criminals and crime syndicates arose and flourished. It has been more than 40 years since Congress passed the current ban on marijuana, inflicting great harm on society just to prohibit a substance far less dangerous than alcohol. - New York Times

It's interesting that the Times would use Prohibition as the leading example of broken legislation. It is obviously correct in noting that alcohol usage certainly didn't stop during this era; if anything, it simply gave the Italian mafia greater influence. (While Prohibition was in full swing, my family began making wine and grappa throughout the Bay Area; then the local mafia began making deadly threats—"provide us with X amount of alcohol, consistently, or have your house 'mysteriously' burned to the ground." It's suspected that the mafia then sold much of my grandparents' products on the black market to increase their steady stream of profits. My family to this day jokingly called it their "insurance.")

You can imagine that making illicit wine quickly loses its charm when it becomes a staple of surviving glorified gang violence. And because humanity never seems to learn from its mistakes, here we are again amid bribes, complicated webs of corruption, extortion and untold violence, but now in the name of marijuana instead of alcohol.

In addition to largely pointless arrests—which, the Times notes likely pander to racial profiling—the pot ban increases bloodshed with illegal drug trafficking. It's no secret that many Mexican cartels smuggle weed into the U.S., as do other drug kingpins operating within our borders. Just two years ago, narcotic ne'er do well Manuel Rodriguez-Perez—a denizen of New York, New Jersey and the Domican Republic—was arrested for his $25 million-dollar bud-smuggling operation. Among other charges of money laundering, obstructing justice and committing perjury, it's also believed he ordered the murders of more than 20 people in order to protect his business.

In 2008 alone, an estimated 6,300 victims lost their lives at the hands of cartel violence. Trafficking drugs like marijuana (and other delectables) provide these cartels with unbelievable power; the U.S. marijuana market alone is estimated at $113 billion.

The repeal of Prohibition in 1933 curbed rising homicide rates and quelled underground violence; it stands to reason that the end of the marijuana prohibition would help do the same. As the Shaffer Library of Drug Policy has put it:

There is no reason to believe that black markets would not disappear with the ending of drug prohibition. Common sense indicates that without the immense profits guaranteed by the necessarily restricted nature of the outlets, there would be little advantage to maintaining such black markets. The current patterns of drug-sale related turf violence would be substantially, if not wholly, undermined. There is no reason to believe that black markets would not disappear with the ending of drug prohibition. Common sense indicates that without the immense profits guaranteed by the necessarily restricted nature of the outlets, there would be little advantage to maintaining such black markets. The current patterns of drug-sale related turf violence would be substantially, if not wholly, undermined.

Substantially, if not wholly, undermining turf violence? We're going to have to agree with The New York Times here: It's high time (pun intended) to once again reverse a dangerous ban.